Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Watto here with America’s primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, ready to talk about bipolar disorder?

We had a fantastic discussion with Dr Kevin Johns about bipolar disorder. Is this an easy diagnosis? Is the diagnosis delayed by years? Can you make it at one visit? What questions should I be asking to uncover this condition?

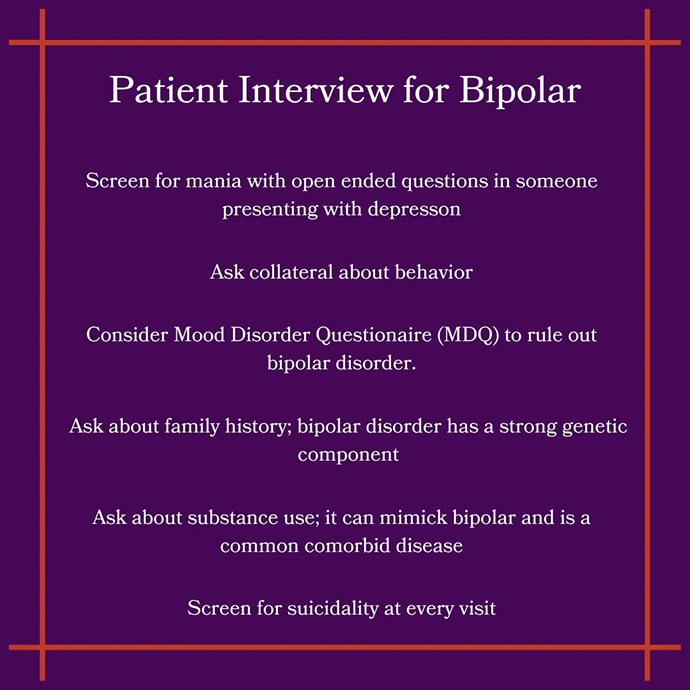

Paul N. Williams, MD: This came up over and over. It’s a hard diagnosis to make. Dr. Johns made the point that he might see a patient for a first visit and say, “I’m leaning toward a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, but it’s going to take some time for me to get to know you before I can make the diagnosis.” So it takes time.

Collateral information is helpful. Many patients don’t understand what bipolar is. It requires a sustained period where the patient is behaving differently. Typically, this manifests as depression the first time through, but he asks patients to make sure there is no history of mania: “Has there ever been a week where you had increased energy, or people thought you were behaving differently, or you were more irritable?”

Watto: Dr Johns said that patients can be both happy and sad — feeling euphoric and crying at the same time.

When you start treatment for bipolar disorder, you may have incomplete information, especially as a primary care clinician meeting the patient for the first time. When I’m starting medication for depression, especially in younger folks, I always worry whether I will accidentally prescribe a medication that might worsen things.

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview is a bipolar screening scale. It’s a script that goes through questions to help you make the diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

But let’s say we’ve already diagnosed someone. Dr Johns talked about the counseling he uses with these patients and family members to support as healthy a lifestyle as possible. Make sure they are getting restful sleep, not experiencing sleep deprivation, and eating a healthy diet — all the things that can promote mental health as well. Talk to family members about looking out for early signs such as changes in behavior or increased irritability. If those occur, bring the patient in right away to adjust their meds and find out what’s going on.

What medications should we think about for bipolar disorder? How would you tackle this?

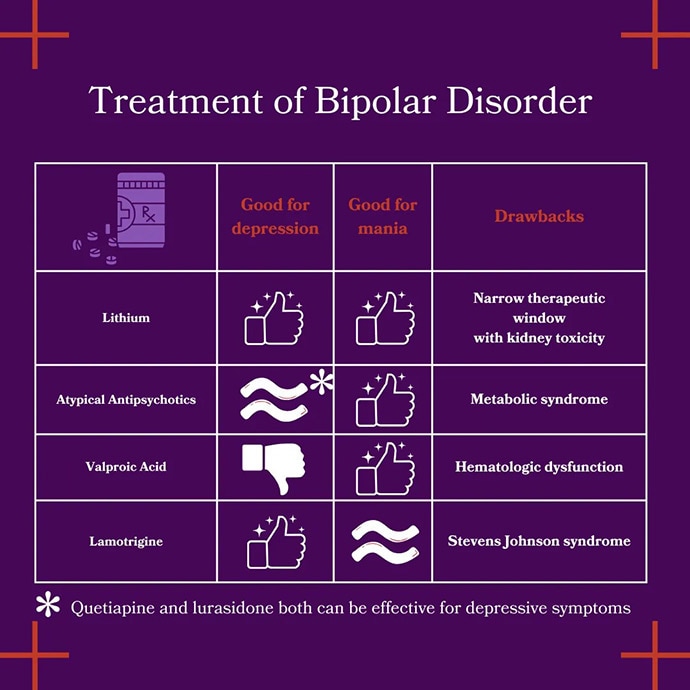

Williams: You mentioned the healthy and therapeutic lifestyle factors, which are important because many of these medications can contribute to metabolic syndrome. In terms of what we might feel comfortable starting in the primary care setting, we talked about quetiapine, which we’ve all had some exposure to. Lurasidone is another drug that we feel reasonably comfortable prescribing.

Other medications that make me a little bit more nervous because of their side effect profiles and narrow therapeutic windows include lamotrigine and lithium.

I’m going to ask you a question for a change: We want to make sure the patient doesn’t have mania; do all of these drugs treat major depression equally well?

Watto: Lurasidone and quetiapine can both treat bipolar depression. Lamotrigine can also treat depression, but because it must be started slowly and titrated up to prevent Stevens-Johnson syndrome, it isn’t a great choice to treat the acute phase of depression. All of the atypical antipsychotics can work for acute mania, but not all of them work for bipolar depression. Depression is the most common phase in bipolar disorder. Patients will have more depression than mania. That’s why we use lurasidone and quetiapine.

Lithium causes many drug-drug interactions and long-term risks with the kidneys and diabetes insipidus so it’s probably best managed by a psychiatrist unless you have the training and feel comfortable prescribing it.

Williams: That was the most conceptually eye-opening fact for me. Depression in bipolar disorder is managed differently from depression in major depressive disorder. Bipolar depression isn’t fundamentally responsive to the same treatments that we would use for major depression. It’s not something I had thought about before.

Watto: That might have been a pearl I dusted off; the idea that if you prescribe a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for bipolar depression, it could precipitate mania and cause rapid cycling of depression and mania. However I didn’t realize that it was also that the type of depression is different in the two disorders, so they may not respond to the same medications. You could be delaying effective treatment by giving patients an SSRI. Even if it doesn’t cause rapid cycling or mania, you could still cause harm by not giving them the most effective treatment.